Photons

A photon is a type of elementary particle, the quantum of the electromagnetic field including electromagnetic radiation such as light, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force (even when static via virtual photons). The photon has zero rest mass and always moves at the speed of light within a vacuum.

Like all elementary particles, photons are currently best explained by quantum mechanics and exhibit wave–particle duality, exhibiting properties of both waves and particles. For example, a single photon may be refracted by a lens and exhibit wave interference with itself, and it can behave as a particle with definite and finite measurable position or momentum, though not both at the same time. The photon’s wave and quanta qualities are two observable aspects of a single phenomenon, and cannot be described by any mechanical model;[2] a representation of this dual property of light, which assumes certain points on the wavefront to be the seat of the energy, is not possible. The quanta in a light wave cannot be spatially localized. Some defined physical parameters of a photon are listed.

The modern concept of the photon was developed gradually by Albert Einstein in the early 20th century to explain experimental observations that did not fit the classical wave model of light. The benefit of the photon model was that it accounted for the frequency dependence of light’s energy, and explained the ability of matter and electromagnetic radiation to be in thermal equilibrium. The photon model accounted for anomalous observations, including the properties of black-body radiation, that others (notably Max Planck) had tried to explain using semiclassical models. In that model, light was described by Maxwell’s equations, but material objects emitted and absorbed light in quantized amounts (i.e., they change energy only by certain particular discrete amounts). Although these semiclassical models contributed to the development of quantum mechanics, many further experiments[3][4] beginning with the phenomenon of Compton scattering of single photons by electrons, validated Einstein’s hypothesis that light itself is quantized.[5][6] In 1926 the optical physicist Frithiof Wolfers and the chemist Gilbert N. Lewis coined the name photon for these particles.[7] After Arthur H. Compton won the Nobel Prize in 1927 for his scattering studies,[8] most scientists accepted that light quanta have an independent existence, and the term photon was accepted.

In the Standard Model of particle physics, photons and other elementary particles are described as a necessary consequence of physical laws having a certain symmetry at every point in spacetime. The intrinsic properties of particles, such as charge, mass and spin, are determined by this gauge symmetry. The photon concept has led to momentous advances in experimental and theoretical physics, including lasers, Bose–Einstein condensation, quantum field theory, and the probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics. It has been applied to photochemistry, high-resolution microscopy, and measurements of molecular distances. Recently, photons have been studied as elements of quantum computers, and for applications in optical imaging and optical communication such as quantum cryptography

Nomenclature

In 1900, the German physicist Max Planck was studying black-body radiation and suggested that the energy carried by electromagnetic waves could only be released in “packets” of energy. In his 1901 article [9] in Annalen der Physik he called these packets “energy elements”. The word quanta (singular quantum, Latin for how much) was used before 1900 to mean particles or amounts of different quantities, including electricity. In 1905, Albert Einstein suggested that electromagnetic waves could only exist as discrete wave-packets.[10] He called such a wave-packet the light quantum (German: das Lichtquant).[Note 1] The name photon derives from the Greek word for light, φῶς (transliterated phôs). Arthur Compton used photon in 1928, referring to Gilbert N. Lewis.[11] The same name was used earlier, by the American physicist and psychologist Leonard T. Troland, who coined the word in 1916, in 1921 by the Irish physicist John Joly, in 1924 by the French physiologist René Wurmser (1890-1993) and in 1926 by the French physicist Frithiof Wolfers (1891-1971).[7] The name was suggested initially as a unit related to the illumination of the eye and the resulting sensation of light and was used later in a physiological context. Although Wolfers’s and Lewis’s theories were contradicted by many experiments and never accepted, the new name was adopted very soon by most physicists after Compton used it.[7][Note 2]

In physics, a photon is usually denoted by the symbol γ (the Greek letter gamma). This symbol for the photon probably derives from gamma rays, which were discovered in 1900 by Paul Villard,[12][13] named by Ernest Rutherford in 1903, and shown to be a form of electromagnetic radiation in 1914 by Rutherford and Edward Andrade.[14] In chemistry and optical engineering, photons are usually symbolized by hν, the energy of a photon, where h is Planck’s constant and the Greek letter ν (nu) is the photon’s frequency.[15] Much less commonly, the photon can be symbolized by hf, where its frequency is denoted by f.

Physical properties

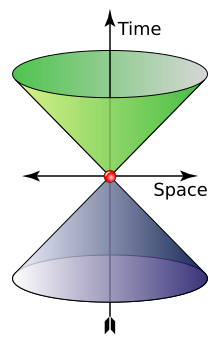

A photon is massless,[Note 3] has no electric charge,[16] and is a stable particle. A photon has two possible polarization states.[17] In the momentum representation of the photon, which is preferred in quantum field theory, a photon is described by its wave vector, which determines its wavelength λ and its direction of propagation. A photon’s wave vector may not be zero and can be represented either as a spatial 3-vector or as a (relativistic) four-vector; in the latter case it belongs to the light cone (pictured). Different signs of the four-vector denote different circular polarizations, but in the 3-vector representation one should account for the polarization state separately; it actually is a spin quantum number. In both cases the space of possible wave vectors is three-dimensional.

The photon is the gauge boson for electromagnetism,[18]:29–30 and therefore all other quantum numbers of the photon (such as lepton number, baryon number, and flavour quantum numbers) are zero.[19] Also, the photon does not obey the Pauli exclusion principle.[20]:1221

Photons are emitted in many natural processes. For example, when a charge is accelerated it emits synchrotron radiation. During a molecular, atomic or nuclear transition to a lower energy level, photons of various energy will be emitted, ranging from radio waves to gamma rays. Photons can also be emitted when a particle and its corresponding antiparticle are annihilated (for example, electron–positron annihilation).[20]:572, 1114, 1172

In empty space, the photon moves at c (the speed of light) and its energy and momentum are related by E = pc, where p is the magnitude of the momentum vector p. This derives from the following relativistic relation, with m = 0:[21]

- E 2 = p 2 c 2 + m 2 c 4 . {\displaystyle E^{2}=p^{2}c^{2}+m^{2}c^{4}.}

The energy and momentum of a photon depend only on its frequency (ν) or inversely, its wavelength (λ):

- E = ℏ ω = h ν = h c λ {\displaystyle E=\hbar \omega =h\nu ={\frac {hc}{\lambda }}}

- p = ℏ k , {\displaystyle {\boldsymbol {p}}=\hbar {\boldsymbol {k}},}

where k is the wave vector (where the wave number k = |k| = 2π/λ), ω = 2πν is the angular frequency, and ħ = h/2π is the reduced Planck constant.[22]

Since p points in the direction of the photon’s propagation, the magnitude of the momentum is

- p = ℏ k = h ν c = h λ . {\displaystyle p=\hbar k={\frac {h\nu }{c}}={\frac {h}{\lambda }}.}

The photon also carries a quantity called spin angular momentum that does not depend on its frequency.[23] The magnitude of its spin is 2 ℏ {\displaystyle \scriptstyle {{\sqrt {2}}\hbar }}

To illustrate the significance of these formulae, the annihilation of a particle with its antiparticle in free space must result in the creation of at least two photons for the following reason. In the center of momentum frame, the colliding antiparticles have no net momentum, whereas a single photon always has momentum (since, as we have seen, it is determined by the photon’s frequency or wavelength, which cannot be zero). Hence, conservation of momentum (or equivalently, translational invariance) requires that at least two photons are created, with zero net momentum. (However, it is possible if the system interacts with another particle or field for the annihilation to produce one photon, as when a positron annihilates with a bound atomic electron, it is possible for only one photon to be emitted, as the nuclear Coulomb field breaks translational symmetry.)[25]:64–65 The energy of the two photons, or, equivalently, their frequency, may be determined from conservation of four-momentum. Seen another way, the photon can be considered as its own antiparticle. The reverse process, pair production, is the dominant mechanism by which high-energy photons such as gamma rays lose energy while passing through matter.[26] That process is the reverse of “annihilation to one photon” allowed in the electric field of an atomic nucleus.

The classical formulae for the energy and momentum of electromagnetic radiation can be re-expressed in terms of photon events. For example, the pressure of electromagnetic radiation on an object derives from the transfer of photon momentum per unit time and unit area to that object, since pressure is force per unit area and force is the change in momentum per unit time.[27]

Each photon carries two distinct and independent forms of angular momentum of light. The spin angular momentum of light of a particular photon is always either + ℏ {\displaystyle +\hbar }

Experimental checks on photon mass

Current commonly accepted physical theories imply or assume the photon to be strictly massless. If the photon is not a strictly massless particle, it would not move at the exact speed of light, c in vacuum. Its speed would be lower and depend on its frequency. Relativity would be unaffected by this; the so-called speed of light, c, would then not be the actual speed at which light moves, but a constant of nature which is the upper bound on speed that any object could theoretically attain in space-time.[29] Thus, it would still be the speed of space-time ripples (gravitational waves and gravitons), but it would not be the speed of photons.

If a photon did have non-zero mass, there would be other effects as well. Coulomb’s law would be modified and the electromagnetic field would have an extra physical degree of freedom. These effects yield more sensitive experimental probes of the photon mass than the frequency dependence of the speed of light. If Coulomb’s law is not exactly valid, then that would allow the presence of an electric field to exist within a hollow conductor when it is subjected to an external electric field. This thus allows one to test Coulomb’s law to very high precision.[30] A null result of such an experiment has set a limit of m ≲ 10−14 eV/c2.[31]

Sharper upper limits on the speed of light have been obtained in experiments designed to detect effects caused by the galactic vector potential. Although the galactic vector potential is very large because the galactic magnetic field exists on very great length scales, only the magnetic field would be observable if the photon is massless. In the case that the photon has mass, the mass term 1 2 m 2 A μ A μ {\displaystyle \scriptstyle {\frac {1}{2}}m^{2}A_{\mu }A^{\mu }}

These sharp limits from the non-observation of the effects caused by the galactic vector potential have been shown to be model dependent.[35] If the photon mass is generated via the Higgs mechanism then the upper limit of m≲10−14 eV/c2 from the test of Coulomb’s law is valid.

Photons inside superconductors do develop a nonzero effective rest mass; as a result, electromagnetic forces become short-range inside superconductors.[36]

Historical development

In most theories up to the eighteenth century, light was pictured as being made up of particles. Since particle models cannot easily account for the refraction, diffraction and birefringence of light, wave theories of light were proposed by René Descartes (1637),[37] Robert Hooke (1665),[38] and Christiaan Huygens (1678);[39] however, particle models remained dominant, chiefly due to the influence of Isaac Newton.[40] In the early nineteenth century, Thomas Young and August Fresnel clearly demonstrated the interference and diffraction of light and by 1850 wave models were generally accepted.[41] In 1865, James Clerk Maxwell‘s prediction[42] that light was an electromagnetic wave—which was confirmed experimentally in 1888 by Heinrich Hertz‘s detection of radio waves[43]—seemed to be the final blow to particle models of light.

The Maxwell wave theory, however, does not account for all properties of light. The Maxwell theory predicts that the energy of a light wave depends only on its intensity, not on its frequency; nevertheless, several independent types of experiments show that the energy imparted by light to atoms depends only on the light’s frequency, not on its intensity. For example, some chemical reactions are provoked only by light of frequency higher than a certain threshold; light of frequency lower than the threshold, no matter how intense, does not initiate the reaction. Similarly, electrons can be ejected from a metal plate by shining light of sufficiently high frequency on it (the photoelectric effect); the energy of the ejected electron is related only to the light’s frequency, not to its intensity.[44][Note 4]

At the same time, investigations of blackbody radiation carried out over four decades (1860–1900) by various researchers[45] culminated in Max Planck‘s hypothesis[9][46] that the energy of any system that absorbs or emits electromagnetic radiation of frequency ν is an integer multiple of an energy quantum E = hν. As shown by Albert Einstein,[10][47] some form of energy quantization must be assumed to account for the thermal equilibrium observed between matter and electromagnetic radiation; for this explanation of the photoelectric effect, Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics.[48]

Since the Maxwell theory of light allows for all possible energies of electromagnetic radiation, most physicists assumed initially that the energy quantization resulted from some unknown constraint on the matter that absorbs or emits the radiation. In 1905, Einstein was the first to propose that energy quantization was a property of electromagnetic radiation itself.[10] Although he accepted the validity of Maxwell’s theory, Einstein pointed out that many anomalous experiments could be explained if the energy of a Maxwellian light wave were localized into point-like quanta that move independently of one another, even if the wave itself is spread continuously over space.[10] In 1909[47] and 1916,[49] Einstein showed that, if Planck’s law of black-body radiation is accepted, the energy quanta must also carry momentum p = h/λ, making them full-fledged particles. This photon momentum was observed experimentally[50] by Arthur Compton, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1927. The pivotal question was then: how to unify Maxwell’s wave theory of light with its experimentally observed particle nature? The answer to this question occupied Albert Einstein for the rest of his life,[51] and was solved in quantum electrodynamics and its successor, the Standard Model (see Second quantization and The photon as a gauge boson, below).

Einstein’s light quantum

Unlike Planck, Einstein entertained the possibility that there might be actual physical quanta of light—what we now call photons. He noticed that a light quantum with energy proportional to its frequency would explain a number of troubling puzzles and paradoxes, including an unpublished law by Stokes, the ultraviolet catastrophe, and the photoelectric effect. Stokes’s law said simply that the frequency of fluorescent light cannot be greater than the frequency of the light (usually ultraviolet) inducing it. Einstein eliminated the ultraviolet catastrophe by imagining a gas of photons behaving like a gas of electrons that he had previously considered. He was advised by a colleague to be careful how he wrote up this paper, in order to not challenge Planck, a powerful figure in physics, too directly, and indeed the warning was justified, as Planck never forgave him for writing it.[52]

Early objections

Einstein’s 1905 predictions were verified experimentally in several ways in the first two decades of the 20th century, as recounted in Robert Millikan‘s Nobel lecture.[53] However, before Compton’s experiment[50] showed that photons carried momentum proportional to their wave number (1922), most physicists were reluctant to believe that electromagnetic radiation itself might be particulate. (See, for example, the Nobel lectures of Wien,[45] Planck[46] and Millikan.[53]) Instead, there was a widespread belief that energy quantization resulted from some unknown constraint on the matter that absorbed or emitted radiation. Attitudes changed over time. In part, the change can be traced to experiments such as Compton scattering, where it was much more difficult not to ascribe quantization to light itself to explain the observed results.[54]

Even after Compton’s experiment, Niels Bohr, Hendrik Kramers and John Slater made one last attempt to preserve the Maxwellian continuous electromagnetic field model of light, the so-called BKS model.[55] To account for the data then available, two drastic hypotheses had to be made:

- Energy and momentum are conserved only on the average in interactions between matter and radiation, but not in elementary processes such as absorption and emission. This allows one to reconcile the discontinuously changing energy of the atom (the jump between energy states) with the continuous release of energy as radiation.

- Causality is abandoned. For example, spontaneous emissions are merely emissions stimulated by a “virtual” electromagnetic field.

However, refined Compton experiments showed that energy–momentum is conserved extraordinarily well in elementary processes; and also that the jolting of the electron and the generation of a new photon in Compton scattering obey causality to within 10 ps. Accordingly, Bohr and his co-workers gave their model “as honorable a funeral as possible”.[51] Nevertheless, the failures of the BKS model inspired Werner Heisenberg in his development of matrix mechanics.[56]

A few physicists persisted[57] in developing semiclassical models in which electromagnetic radiation is not quantized, but matter appears to obey the laws of quantum mechanics. Although the evidence from chemical and physical experiments for the existence of photons was overwhelming by the 1970s, this evidence could not be considered as absolutely definitive; since it relied on the interaction of light with matter, and a sufficiently complete theory of matter could in principle account for the evidence. Nevertheless, all semiclassical theories were refuted definitively in the 1970s and 1980s by photon-correlation experiments.[Note 5] Hence, Einstein’s hypothesis that quantization is a property of light itself is considered to be proven.

Wave–particle duality and uncertainty principles

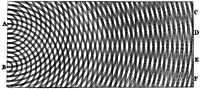

Photons, like all quantum objects, exhibit wave-like and particle-like properties. Their dual wave–particle nature can be difficult to visualize. The photon displays clearly wave-like phenomena such as diffraction and interference on the length scale of its wavelength. For example, a single photon passing through a double-slit experiment exhibits interference phenomena but only if no measure was made at the slit. A single photon passing through a double-slit experiment lands on the screen with a probability distribution given by its interference pattern determined by Maxwell’s equations.[58] However, experiments confirm that the photon is not a short pulse of electromagnetic radiation; it does not spread out as it propagates, nor does it divide when it encounters a beam splitter.[59] Rather, the photon seems to be a point-like particle since it is absorbed or emitted as a whole by arbitrarily small systems, systems much smaller than its wavelength, such as an atomic nucleus (≈10−15 m across) or even the point-like electron. Nevertheless, the photon is not a point-like particle whose trajectory is shaped probabilistically by the electromagnetic field, as conceived by Einstein and others; that hypothesis was also refuted by the photon-correlation experiments cited above. According to our present understanding, the electromagnetic field itself is produced by photons, which in turn result from a local gauge symmetry and the laws of quantum field theory (see the Second quantization and Gauge boson sections below).

A key element of quantum mechanics is Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, which forbids the simultaneous measurement of the position and momentum of a particle along the same direction. Remarkably, the uncertainty principle for charged, material particles requires the quantization of light into photons, and even the frequency dependence of the photon’s energy and momentum.

An elegant illustration of the uncertainty principle is Heisenberg’s thought experiment for locating an electron with an ideal microscope.[60] The position of the electron can be determined to within the resolving power of the microscope, which is given by a formula from classical optics

- Δ x ∼ λ sin θ {\displaystyle \Delta x\sim {\frac {\lambda }{\sin \theta }}}

where θ is the aperture angle of the microscope and λ is the wavelength of the light used to observe the electron. Thus, the position uncertainty Δ x {\displaystyle \Delta x}

- Δ p ∼ p photon sin θ = h λ sin θ {\displaystyle \Delta p\sim p_{\text{photon}}\sin \theta ={\frac {h}{\lambda }}\sin \theta }

giving the product Δ x Δ p ∼ h {\displaystyle \Delta x\Delta p\,\sim \,h}

The analogous uncertainty principle for photons forbids the simultaneous measurement of the number n {\displaystyle n}

- Δ n Δ ϕ > 1 {\displaystyle \Delta n\Delta \phi >1}

See coherent state and squeezed coherent state for more details.

Both photons and electrons create analogous interference patterns when passed through a double-slit experiment. For photons, this corresponds to the interference of a Maxwell light wave whereas, for material particles (electron), this corresponds to the interference of the Schrödinger wave equation. Although this similarity might suggest that Maxwell’s equations describing the photon’s electromagnetic wave are simply Schrödinger’s equation for photons, most physicists do not agree.[62][63] For one thing, they are mathematically different; most obviously, Schrödinger’s one equation for the electron solves for a complex field, whereas Maxwell’s four equations solve for real fields. More generally, the normal concept of a Schrödinger probability wave function cannot be applied to photons.[64] As photons are massless, they cannot be localized without being destroyed; technically, photons cannot have a position eigenstate | r ⟩ {\displaystyle |\mathbf {r} \rangle }

Another interpretation, that avoids duality, is the De Broglie–Bohm theory: known also as the pilot-wave model. In that theory, the photon is both, wave and particle.[69] “This idea seems to me so natural and simple, to resolve the wave-particle dilemma in such a clear and ordinary way, that it is a great mystery to me that it was so generally ignored”,[70] J.S.Bell.

Bose–Einstein model of a photon gas

In 1924, Satyendra Nath Bose derived Planck’s law of black-body radiation without using any electromagnetism, but rather by using a modification of coarse-grained counting of phase space.[71] Einstein showed that this modification is equivalent to assuming that photons are rigorously identical and that it implied a “mysterious non-local interaction”,[72][73] now understood as the requirement for a symmetric quantum mechanical state. This work led to the concept of coherent states and the development of the laser. In the same papers, Einstein extended Bose’s formalism to material particles (bosons) and predicted that they would condense into their lowest quantum state at low enough temperatures; this Bose–Einstein condensation was observed experimentally in 1995.[74] It was later used by Lene Hau to slow, and then completely stop, light in 1999[75] and 2001.[76]

The modern view on this is that photons are, by virtue of their integer spin, bosons (as opposed to fermions with half-integer spin). By the spin-statistics theorem, all bosons obey Bose–Einstein statistics (whereas all fermions obey Fermi–Dirac statistics).[77]

Stimulated and spontaneous emission

In 1916, Albert Einstein showed that Planck’s radiation law could be derived from a semi-classical, statistical treatment of photons and atoms, which implies a link between the rates at which atoms emit and absorb photons. The condition follows from the assumption that functions of the emission and absorption of radiation by the atoms are independent of each other, and that thermal equilibrium is made by way of the radiation’s interaction with the atoms. Consider a cavity in thermal equilibrium with all parts of itself and filled with electromagnetic radiation and that the atoms can emit and absorb that radiation. Thermal equilibrium requires that the energy density ρ ( ν ) {\displaystyle \rho (\nu )}

Einstein began by postulating simple proportionality relations for the different reaction rates involved. In his model, the rate R j i {\displaystyle R_{ji}}

- R j i = N j B j i ρ ( ν ) {\displaystyle R_{ji}=N_{j}B_{ji}\rho (\nu )\!}

where B j i {\displaystyle B_{ji}}

- R i j = N i A i j + N i B i j ρ ( ν ) {\displaystyle R_{ij}=N_{i}A_{ij}+N_{i}B_{ij}\rho (\nu )\!}

where A i j {\displaystyle A_{ij}}

- A i j = 8 π h ν 3 c 3 B i j . {\displaystyle A_{ij}={\frac {8\pi h\nu ^{3}}{c^{3}}}B_{ij}.}

The A and Bs are collectively known as the Einstein coefficients.[79]

Einstein could not fully justify his rate equations, but claimed that it should be possible to calculate the coefficients A i j {\displaystyle A_{ij}}

Einstein was troubled by the fact that his theory seemed incomplete, since it did not determine the direction of a spontaneously emitted photon. A probabilistic nature of light-particle motion was first considered by Newton in his treatment of birefringence and, more generally, of the splitting of light beams at interfaces into a transmitted beam and a reflected beam. Newton hypothesized that hidden variables in the light particle determined which of the two paths a single photon would take.[40] Similarly, Einstein hoped for a more complete theory that would leave nothing to chance, beginning his separation[51] from quantum mechanics. Ironically, Max Born‘s probabilistic interpretation of the wave function[87][88] was inspired by Einstein’s later work searching for a more complete theory.[89]

Second quantization and high energy photon interactions

In 1910, Peter Debye derived Planck’s law of black-body radiation from a relatively simple assumption.[90] He correctly decomposed the electromagnetic field in a cavity into its Fourier modes, and assumed that the energy in any mode was an integer multiple of h ν {\displaystyle h\nu }

In 1925, Born, Heisenberg and Jordan reinterpreted Debye’s concept in a key way.[91] As may be shown classically, the Fourier modes of the electromagnetic field—a complete set of electromagnetic plane waves indexed by their wave vector k and polarization state—are equivalent to a set of uncoupled simple harmonic oscillators. Treated quantum mechanically, the energy levels of such oscillators are known to be E = n h ν {\displaystyle E=nh\nu }

Dirac took this one step further.[82][83] He treated the interaction between a charge and an electromagnetic field as a small perturbation that induces transitions in the photon states, changing the numbers of photons in the modes, while conserving energy and momentum overall. Dirac was able to derive Einstein’s A i j {\displaystyle A_{ij}}

Dirac’s second-order perturbation theory can involve virtual photons, transient intermediate states of the electromagnetic field; the static electric and magnetic interactions are mediated by such virtual photons. In such quantum field theories, the probability amplitude of observable events is calculated by summing over all possible intermediate steps, even ones that are unphysical; hence, virtual photons are not constrained to satisfy E = p c {\displaystyle E=pc}

Other virtual particles may contribute to the summation as well; for example, two photons may interact indirectly through virtual electron–positron pairs.[92] In fact, such photon-photon scattering (see two-photon physics), as well as electron-photon scattering, is meant to be one of the modes of operations of the planned particle accelerator, the International Linear Collider.[93]

In modern physics notation, the quantum state of the electromagnetic field is written as a Fock state, a tensor product of the states for each electromagnetic mode

- | n k 0 ⟩ ⊗ | n k 1 ⟩ ⊗ ⋯ ⊗ | n k n ⟩ … {\displaystyle |n_{k_{0}}\rangle \otimes |n_{k_{1}}\rangle \otimes \dots \otimes |n_{k_{n}}\rangle \dots }

where | n k i ⟩ {\displaystyle |n_{k_{i}}\rangle }

The hadronic properties of the photon

Measurements of the interaction between energetic photons and hadrons show that the interaction is much more intense than expected by the interaction of merely photons with the hadron’s electric charge. Furthermore, the interaction of energetic photons with protons is similar to the interaction of photons with neutrons[94] in spite of the fact that the electric charge structures of protons and neutrons are substantially different. A theory called Vector Meson Dominance (VMD) was developed to explain this effect. According to VMD, the photon is a superposition of the pure electromagnetic photon which interacts only with electric charges and vector meson.[95] However, if experimentally probed at very short distances, the intrinsic structure of the photon is recognized as a flux of quark and gluon components, quasi-free according to asymptotic freedom in QCD and described by the photon structure function.[96][97] A comprehensive comparison of data with theoretical predictions was presented in a review in 2000.[98]

The photon as a gauge boson

The electromagnetic field can be understood as a gauge field, i.e., as a field that results from requiring that a gauge symmetry holds independently at every position in spacetime.[99] For the electromagnetic field, this gauge symmetry is the Abelian U(1) symmetry of complex numbers of absolute value 1, which reflects the ability to vary the phase of a complex field without affecting observables or real valued functions made from it, such as the energy or the Lagrangian.

The quanta of an Abelian gauge field must be massless, uncharged bosons, as long as the symmetry is not broken; hence, the photon is predicted to be massless, and to have zero electric charge and integer spin. The particular form of the electromagnetic interaction specifies that the photon must have spin ±1; thus, its helicity must be ± ℏ {\displaystyle \pm \hbar }

In the prevailing Standard Model of physics, the photon is one of four gauge bosons in the electroweak interaction; the other three are denoted W+, W− and Z0 and are responsible for the weak interaction. Unlike the photon, these gauge bosons have mass, owing to a mechanism that breaks their SU(2) gauge symmetry. The unification of the photon with W and Z gauge bosons in the electroweak interaction was accomplished by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg, for which they were awarded the 1979 Nobel Prize in physics.[100][101][102] Physicists continue to hypothesize grand unified theories that connect these four gauge bosons with the eight gluon gauge bosons of quantum chromodynamics; however, key predictions of these theories, such as proton decay, have not been observed experimentally.[103]

Contributions to the mass of a system

The energy of a system that emits a photon is decreased by the energy E {\displaystyle E}

This concept is applied in key predictions of quantum electrodynamics (QED, see above). In that theory, the mass of electrons (or, more generally, leptons) is modified by including the mass contributions of virtual photons, in a technique known as renormalization. Such “radiative corrections” contribute to a number of predictions of QED, such as the magnetic dipole moment of leptons, the Lamb shift, and the hyperfine structure of bound lepton pairs, such as muonium and positronium.[105]

Since photons contribute to the stress–energy tensor, they exert a gravitational attraction on other objects, according to the theory of general relativity. Conversely, photons are themselves affected by gravity; their normally straight trajectories may be bent by warped spacetime, as in gravitational lensing, and their frequencies may be lowered by moving to a higher gravitational potential, as in the Pound–Rebka experiment. However, these effects are not specific to photons; exactly the same effects would be predicted for classical electromagnetic waves.[106]

Photons in matter

Light that travels through transparent matter does so at a lower speed than c, the speed of light in a vacuum. For example, photons engage in so many collisions on the way from the core of the sun that radiant energy can take about a million years to reach the surface;[107] however, once in open space, a photon takes only 8.3 minutes to reach Earth. The factor by which the speed is decreased is called the refractive index of the material. In a classical wave picture, the slowing can be explained by the light inducing electric polarization in the matter, the polarized matter radiating new light, and that new light interfering with the original light wave to form a delayed wave. In a particle picture, the slowing can instead be described as a blending of the photon with quantum excitations of the matter to produce quasi-particles known as polariton (other quasi-particles are phonons and excitons); this polariton has a nonzero effective mass, which means that it cannot travel at c. Light of different frequencies may travel through matter at different speeds; this is called dispersion (not to be confused with scattering). In some cases, it can result in extremely slow speeds of light in matter. The effects of photon interactions with other quasi-particles may be observed directly in Raman scattering and Brillouin scattering.[108]

Photons can also be absorbed by nuclei, atoms or molecules, provoking transitions between their energy levels. A classic example is the molecular transition of retinal (C20H28O), which is responsible for vision, as discovered in 1958 by Nobel laureate biochemist George Wald and co-workers. The absorption provokes a cis-trans isomerization that, in combination with other such transitions, is transduced into nerve impulses. The absorption of photons can even break chemical bonds, as in the photodissociation of chlorine; this is the subject of photochemistry.[109][110]

Technological applications

Photons have many applications in technology. These examples are chosen to illustrate applications of photons per se, rather than general optical devices such as lenses, etc. that could operate under a classical theory of light. The laser is an extremely important application and is discussed above under stimulated emission.

Individual photons can be detected by several methods. The classic photomultiplier tube exploits the photoelectric effect: a photon of sufficient energy strikes a metal plate and knocks free an electron, initiating an ever-amplifying avalanche of electrons. Semiconductor charge-coupled device chips use a similar effect: an incident photon generates a charge on a microscopic capacitor that can be detected. Other detectors such as Geiger counters use the ability of photons to ionize gas molecules contained in the device, causing a detectable change of conductivity of the gas.[111]

Planck’s energy formula E = h ν {\displaystyle E=h\nu }

Under some conditions, an energy transition can be excited by “two” photons that individually would be insufficient. This allows for higher resolution microscopy, because the sample absorbs energy only in the spectrum where two beams of different colors overlap significantly, which can be made much smaller than the excitation volume of a single beam (see two-photon excitation microscopy). Moreover, these photons cause less damage to the sample, since they are of lower energy.[112]

In some cases, two energy transitions can be coupled so that, as one system absorbs a photon, another nearby system “steals” its energy and re-emits a photon of a different frequency. This is the basis of fluorescence resonance energy transfer, a technique that is used in molecular biology to study the interaction of suitable proteins.[113]

Several different kinds of hardware random number generators involve the detection of single photons. In one example, for each bit in the random sequence that is to be produced, a photon is sent to a beam-splitter. In such a situation, there are two possible outcomes of equal probability. The actual outcome is used to determine whether the next bit in the sequence is “0” or “1”.[114][115]

Recent research

Much research has been devoted to applications of photons in the field of quantum optics. Photons seem well-suited to be elements of an extremely fast quantum computer, and the quantum entanglement of photons is a focus of research. Nonlinear optical processes are another active research area, with topics such as two-photon absorption, self-phase modulation, modulational instability and optical parametric oscillators. However, such processes generally do not require the assumption of photons per se; they may often be modeled by treating atoms as nonlinear oscillators. The nonlinear process of spontaneous parametric down conversion is often used to produce single-photon states. Finally, photons are essential in some aspects of optical communication, especially for quantum cryptography.[Note 6]

See also

- Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory

- Ballistic photon

- Dirac equation

- Doppler effect

- Electromagnetic radiation

- EPR paradox

- High energy X-ray imaging technology

- Laser

- Light

- Luminiferous aether

- Medipix

- Phonon

- Photography

- Photon counting

- Photon energy

- Photon epoch

- Photon polarization

- Photonic molecule

- Photonics

- Quantum optics

- Single photon source

- Static forces and virtual-particle exchange

- Two-photon physics

Notes

- Although the 1967 Elsevier translation of Planck’s Nobel Lecture interprets Planck’s Lichtquant as “photon”, the more literal 1922 translation by Hans Thacher Clarke and Ludwik Silberstein Planck, Max (1922). The Origin and Development of the Quantum Theory. Clarendon Press. (here [1]) uses “light-quantum”. No evidence is known that Planck himself used the term “photon” by 1926 (see also this note).

- Isaac Asimov credits Arthur Compton with defining quanta of energy as photons in 1923. Asimov, Isaac (1 April 1983). The Neutrino: Ghost Particle of the Atom. Garden City (NY): Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-00483-6. and Asimov, Isaac (1 January 1971). The Universe: From Flat Earth to Quasar. New York (NY): Walker. ISBN 0-8027-0316-X. LCCN 66022515.

- The mass of the photon is believed to be exactly zero. Some sources also refer to the relativistic mass, which is just the energy scaled to units of mass. For a photon with wavelength λ or energy E, this is h/λc or E/c2. This usage for the term “mass” is no longer common in scientific literature. Further info: What is the mass of a photon? http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/ParticleAndNuclear/photon_mass.html

- The phrase “no matter how intense” refers to intensities below approximately 1013 W/cm2 at which point perturbation theory begins to break down. In contrast, in the intense regime, which for visible light is above approximately 1014 W/cm2, the classical wave description correctly predicts the energy acquired by electrons, called ponderomotive energy. (See also: Boreham et al. (1996). “Photon density and the correspondence principle of electromagnetic interaction“.) By comparison, sunlight is only about 0.1 W/cm2.

- These experiments produce results that cannot be explained by any classical theory of light, since they involve anticorrelations that result from the quantum measurement process. In 1974, the first such experiment was carried out by Clauser, who reported a violation of a classical Cauchy–Schwarz inequality. In 1977, Kimble et al. demonstrated an analogous anti-bunching effect of photons interacting with a beam splitter; this approach was simplified and sources of error eliminated in the photon-anticorrelation experiment of Grangier et al. (1986). This work is reviewed and simplified further in Thorn et al. (2004). (These references are listed below under #Additional references.)

- Introductory-level material on the various sub-fields of quantum optics can be found in Fox, M. (2006). Quantum Optics: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856673-5.

References

- Amsler, C. (Particle Data Group); Amsler; Doser; Antonelli; Asner; Babu; Baer; Band; Barnett; Bergren; Beringer; Bernardi; Bertl; Bichsel; Biebel; Bloch; Blucher; Blusk; Cahn; Carena; Caso; Ceccucci; Chakraborty; Chen; Chivukula; Cowan; Dahl; d’Ambrosio; Damour; et al. (2008). “Review of Particle Physics: Gauge and Higgs bosons” (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667: 1. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667….1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

- Joos, George (1951). Theoretical Physics. London and Glasgow: Blackie and Son Limited. p. 679.

- Kimble, H.J.; Dagenais, M.; Mandel, L. (1977). “Photon Anti-bunching in Resonance Fluorescence”. Physical Review Letters. 39 (11): 691–695. Bibcode:1977PhRvL..39..691K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.39.691.

- Grangier, P.; Roger, G.; Aspect, A.; Roger; Aspect (1986). “Experimental Evidence for a Photon Anticorrelation Effect on a Beam Splitter: A New Light on Single-Photon Interferences”. Europhysics Letters. 1 (4): 173–179. Bibcode:1986EL……1..173G. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/1/4/004.

- Compton, Arthur H. (12 Dec 1927). “X-rays as a branch of optics” (PDF-1.4). Nobel Lecture.

- “Arthur H. Compton – Nobel Lecture: X-rays as a Branch of Optics”. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 4 Mar 2017. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1927/compton-lecture.html>

- Kragh, Helge (1 January 2014). “Photon: New light on an old name” (PDF-1.5). arXiv:1401.0293

.

. - “Arthur H. Compton – Facts”. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 4 Mar 2017. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1927/compton-facts.html>

- Planck, M. (1901). “Über das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum”. Annalen der Physik (in German). 4 (3): 553–563. Bibcode:1901AnP…309..553P. doi:10.1002/andp.19013090310. English translation

- Einstein, A. (1905). “Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt” (PDF). Annalen der Physik (in German). 17 (6): 132–148. Bibcode:1905AnP…322..132E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220607.. An English translation is available from Wikisource.

- “Discordances entre l’expérience et la théorie électromagnétique du rayonnement.” In Électrons et Photons. Rapports et Discussions de Cinquième Conseil de Physique, edited by Institut International de Physique Solvay. Paris: Gauthier-Villars, pp. 55-85.

- Villard, P. (1900). “Sur la réflexion et la réfraction des rayons cathodiques et des rayons déviables du radium”. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences (in French). 130: 1010–1012.

- Villard, P. (1900). “Sur le rayonnement du radium”. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences (in French). 130: 1178–1179.

- Rutherford, E.; Andrade, E.N.C. (1914). “The Wavelength of the Soft Gamma Rays from Radium B”. Philosophical Magazine. 27 (161): 854–868. doi:10.1080/14786440508635156.

- Andrew Liddle (27 April 2015). An Introduction to Modern Cosmology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-118-69025-3.

- Kobychev, V.V.; Popov, S.B. (2005). “Constraints on the photon charge from observations of extragalactic sources”. Astronomy Letters. 31 (3): 147–151. Bibcode:2005AstL…31..147K. arXiv:hep-ph/0411398

. doi:10.1134/1.1883345.

. doi:10.1134/1.1883345. - Matthew D. Schwartz (2014). Quantum Field Theory and the Standard Model. Cambridge University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-107-03473-0.

- Role as gauge boson and polarization section 5.1 inAitchison, I.J.R.; Hey, A.J.G. (1993). Gauge Theories in Particle Physics. IOP Publishing. ISBN 0-85274-328-9.

- See p.31 inAmsler, C.; et al. (2008). “Review of Particle Physics”. Physics Letters B. 667: 1–1340. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667….1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

- Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jerl (2005), Fundamental of Physics (7th ed.), USA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., ISBN 0-471-23231-9

- See section 1.6 in Alonso & Finn 1968, Section 1.6

- Davison E. Soper, Electromagnetic radiation is made of photons, Institute of Theoretical Science, University of Oregon

- This property was experimentally verified by Raman and Bhagavantam in 1931: Raman, C.V.; Bhagavantam, S. (1931). “Experimental proof of the spin of the photon” (PDF). Indian Journal of Physics. 6: 353.

- Burgess, C.; Moore, G. (2007). “1.3.3.2”. The Standard Model. A Primer. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86036-9.

- Griffiths, David J. (2008), Introduction to Elementary Particles (2nd revised ed.), WILEY-VCH, ISBN 978-3-527-40601-2

- Alonso & Finn 1968, Section 9.3

- E.g., Appendix XXXII in Born, Max; Blin-Stoyle, Roger John; Radcliffe, J. M. (1 June 1989). Atomic Physics. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-65984-8.

- Alan E. Willner. “Twisted Light Could Dramatically Boost Data Rates: Orbital angular momentum could take optical and radio communication to new heights”. 2016.

- Mermin, David (February 1984). “Relativity without light”. American Journal of Physics. 52 (2): 119–124. Bibcode:1984AmJPh..52..119M. doi:10.1119/1.13917.

- Plimpton, S.; Lawton, W. (1936). “A Very Accurate Test of Coulomb’s Law of Force Between Charges”. Physical Review. 50 (11): 1066. Bibcode:1936PhRv…50.1066P. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.50.1066.

- Williams, E.; Faller, J.; Hill, H. (1971). “New Experimental Test of Coulomb’s Law: A Laboratory Upper Limit on the Photon Rest Mass”. Physical Review Letters. 26 (12): 721. Bibcode:1971PhRvL..26..721W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.26.721.

- Chibisov, G V (1976). “Astrophysical upper limits on the photon rest mass”. Soviet Physics Uspekhi. 19 (7): 624. Bibcode:1976SvPhU..19..624C. doi:10.1070/PU1976v019n07ABEH005277.

- Lakes, Roderic (1998). “Experimental Limits on the Photon Mass and Cosmic Magnetic Vector Potential”. Physical Review Letters. 80 (9): 1826. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..80.1826L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.1826.

- Amsler, C; Doser, M; Antonelli, M; Asner, D; Babu, K; Baer, H; Band, H; Barnett, R; et al. (2008). “Review of Particle Physics⁎”. Physics Letters B. 667: 1. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667….1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. Summary Table

- Adelberger, Eric; Dvali, Gia; Gruzinov, Andrei (2007). “Photon-Mass Bound Destroyed by Vortices”. Physical Review Letters. 98 (1): 010402. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98a0402A. PMID 17358459. arXiv:hep-ph/0306245

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.010402. preprint

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.010402. preprint - Wilczek, Frank (2010). The Lightness of Being: Mass, Ether, and the Unification of Forces. Basic Books. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-465-01895-6.

- Descartes, R. (1637). Discours de la méthode (Discourse on Method) (in French). Imprimerie de Ian Maire. ISBN 0-268-00870-1.

- Hooke, R. (1667). Micrographia: or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses with observations and inquiries thereupon … London (UK): Royal Society of London. ISBN 0-486-49564-7.

- Huygens, C. (1678). Traité de la lumière (in French).. An English translation is available from Project Gutenberg

- Newton, I. (1952) [1730]. Opticks (4th ed.). Dover (NY): Dover Publications. Book II, Part III, Propositions XII–XX; Queries 25–29. ISBN 0-486-60205-2.

- Buchwald, J.Z. (1989). The Rise of the Wave Theory of Light: Optical Theory and Experiment in the Early Nineteenth Century. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07886-8. OCLC 18069573.

- Maxwell, J.C. (1865). “A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field“. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 155: 459–512. Bibcode:1865RSPT..155..459C. doi:10.1098/rstl.1865.0008. This article followed a presentation by Maxwell on 8 December 1864 to the Royal Society.

- Hertz, H. (1888). “Über Strahlen elektrischer Kraft”. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin) (in German). 1888: 1297–1307.

- Frequency-dependence of luminiscence p. 276f., photoelectric effect section 1.4 in Alonso & Finn 1968

- Wien, W. (1911). “Wilhelm Wien Nobel Lecture”. nobelprize.org.

- Planck, M. (1920). “Max Planck’s Nobel Lecture”. nobelprize.org.

- Einstein, A. (1909). “Über die Entwicklung unserer Anschauungen über das Wesen und die Konstitution der Strahlung” (PDF). Physikalische Zeitschrift (in German). 10: 817–825.. An English translation is available from Wikisource.

- Presentation speech by Svante Arrhenius for the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics, December 10, 1922. Online text from [nobelprize.org], The Nobel Foundation 2008. Access date 2008-12-05.

- Einstein, A. (1916). “Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung”. Mitteilungen der Physikalischen Gesellschaft zu Zürich. 16: 47. Also Physikalische Zeitschrift, 18, 121–128 (1917). (in German)

- Compton, A. (1923). “A Quantum Theory of the Scattering of X-rays by Light Elements”. Physical Review. 21 (5): 483–502. Bibcode:1923PhRv…21..483C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.21.483.

- Pais, A. (1982). Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-853907-X.

- Einstein and the Quantum: The Quest of the Valiant Swabian, A. Douglas Stone, Princeton University Press, 2013.

- Millikan, R.A (1924). “Robert A. Millikan’s Nobel Lecture”.

- Hendry, J. (1980). “The development of attitudes to the wave-particle duality of light and quantum theory, 1900–1920”. Annals of Science. 37 (1): 59–79. doi:10.1080/00033798000200121.

- Bohr, N.; Kramers, H.A.; Slater, J.C. (1924). “The Quantum Theory of Radiation”. Philosophical Magazine. 47: 785–802. doi:10.1080/14786442408565262. Also Zeitschrift für Physik, 24, 69 (1924).

- Heisenberg, W. (1933). “Heisenberg Nobel lecture”.

- Mandel, L. (1976). E. Wolf, ed. “The case for and against semiclassical radiation theory”. Progress in Optics. Progress in Optics. North-Holland. 13: 27–69. ISBN 978-0-444-10806-7. doi:10.1016/S0079-6638(08)70018-0.

- Taylor, G.I. (1909). Interference fringes with feeble light. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 15. pp. 114–115.

- Saleh, B. E. A. & Teich, M. C. (2007). Fundamentals of Photonics. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-35832-0.

- Heisenberg, W. (1927). “Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik”. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 43 (3–4): 172–198. Bibcode:1927ZPhy…43..172H. doi:10.1007/BF01397280.

- E.g., p. 10f. in Schiff, L.I. (1968). Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055287-8.

- Kramers, H.A. (1958). Quantum Mechanics. Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 0-486-49533-7.

- Bohm, D. (1989) [1954]. Quantum Theory. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-65969-0.

- Newton, T.D.; Wigner, E.P. (1949). “Localized states for elementary particles”. Reviews of Modern Physics. 21 (3): 400–406. Bibcode:1949RvMP…21..400N. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.21.400.

- Bialynicki-Birula, I. (1994). “On the wave function of the photon” (PDF). Acta Physica Polonica A. 86: 97–116.

- Sipe, J.E. (1995). “Photon wave functions”. Physical Review A. 52 (3): 1875–1883. Bibcode:1995PhRvA..52.1875S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.1875.

- Bialynicki-Birula, I. (1996). “Photon wave function”. Progress in Optics. Progress in Optics. 36: 245–294. ISBN 978-0-444-82530-8. doi:10.1016/S0079-6638(08)70316-0.

- Scully, M.O.; Zubairy, M.S. (1997). Quantum Optics. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43595-1.

- The best illustration is the Couder experiment, demonstrating the behaviour of a mechanical analog, see Video on YouTube

- Bell, J. S. (3 June 2004). Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics: Collected Papers on Quantum Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52338-7.

- Bose, S.N. (1924). “Plancks Gesetz und Lichtquantenhypothese”. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 26: 178–181. Bibcode:1924ZPhy…26..178B. doi:10.1007/BF01327326.

- Einstein, A. (1924). “Quantentheorie des einatomigen idealen Gases”. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin), Physikalisch-mathematische Klasse (in German). 1924: 261–267.

- Einstein, A. (1925). “Quantentheorie des einatomigen idealen Gases, Zweite Abhandlung”. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin), Physikalisch-mathematische Klasse (in German). 1925: 3–14. ISBN 978-3-527-60895-9. doi:10.1002/3527608958.ch28.

- Anderson, M.H.; Ensher, J.R.; Matthews, M.R.; Wieman, C.E.; Cornell, E.A. (1995). “Observation of Bose–Einstein Condensation in a Dilute Atomic Vapor”. Science. 269 (5221): 198–201. Bibcode:1995Sci…269..198A. JSTOR 2888436. PMID 17789847. doi:10.1126/science.269.5221.198.

- “Physicists Slow Speed of Light”. News.harvard.edu (1999-02-18). Retrieved on 2015-05-11.

- “Light Changed to Matter, Then Stopped and Moved”. photonics.com (February 2007). Retrieved on 2015-05-11.

- Streater, R.F.; Wightman, A.S. (1989). PCT, Spin and Statistics, and All That. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-09410-X.

- Einstein, A. (1916). “Strahlungs-emission und -absorption nach der Quantentheorie”. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft (in German). 18: 318–323. Bibcode:1916DPhyG..18..318E.

- Section 1.4 in Wilson, J.; Hawkes, F.J.B. (1987). Lasers: Principles and Applications. New York: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-523705-X.

- Einstein, A. (1916). “Strahlungs-emission und -absorption nach der Quantentheorie”. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft (in German). 18: 318–323. Bibcode:1916DPhyG..18..318E.

p. 322: Die Konstanten A m n {\displaystyle A_{m}^{n}}

and B m n {\displaystyle B_{m}^{n}}

würden sich direkt berechnen lassen, wenn wir im Besitz einer im Sinne der Quantenhypothese modifizierten Elektrodynamik und Mechanik wären.”

- Dirac, P.A.M. (1926). “On the Theory of Quantum Mechanics”. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 112 (762): 661–677. Bibcode:1926RSPSA.112..661D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1926.0133.

- Dirac, P.A.M. (1927). “The Quantum Theory of the Emission and Absorption of Radiation” (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 114 (767): 243–265. Bibcode:1927RSPSA.114..243D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0039.

- Dirac, P.A.M. (1927b). The Quantum Theory of Dispersion. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 114. pp. 710–728. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0071.

- Heisenberg, W.; Pauli, W. (1929). “Zur Quantentheorie der Wellenfelder”. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 56: 1. Bibcode:1929ZPhy…56….1H. doi:10.1007/BF01340129.

- Heisenberg, W.; Pauli, W. (1930). “Zur Quantentheorie der Wellenfelder”. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 59 (3–4): 139. Bibcode:1930ZPhy…59..168H. doi:10.1007/BF01341423.

- Fermi, E. (1932). “Quantum Theory of Radiation”. Reviews of Modern Physics. 4: 87. Bibcode:1932RvMP….4…87F. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.4.87.

- Born, M. (1926). “Zur Quantenmechanik der Stossvorgänge”. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 37 (12): 863–867. Bibcode:1926ZPhy…37..863B. doi:10.1007/BF01397477.

- Born, M. (1926). “Quantenmechanik der Stossvorgänge”. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 38 (11–12): 803. Bibcode:1926ZPhy…38..803B. doi:10.1007/BF01397184.

- Pais, A. (1986). Inward Bound: Of Matter and Forces in the Physical World. Oxford University Press. p. 260. ISBN 0-19-851997-4. Specifically, Born claimed to have been inspired by Einstein’s never-published attempts to develop a “ghost-field” theory, in which point-like photons are guided probabilistically by ghost fields that follow Maxwell’s equations.

- Debye, P. (1910). “Der Wahrscheinlichkeitsbegriff in der Theorie der Strahlung”. Annalen der Physik (in German). 33 (16): 1427–1434. Bibcode:1910AnP…338.1427D. doi:10.1002/andp.19103381617.

- Born, M.; Heisenberg, W.; Jordan, P. (1925). “Quantenmechanik II”. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 35 (8–9): 557–615. Bibcode:1926ZPhy…35..557B. doi:10.1007/BF01379806.

- Photon-photon-scattering section 7-3-1, renormalization chapter 8-2 in Itzykson, C.; Zuber, J.-B. (1980). Quantum Field Theory. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-032071-3.

- Weiglein, G. (2008). “Electroweak Physics at the ILC”. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 110 (4): 042033. Bibcode:2008JPhCS.110d2033W. arXiv:0711.3003

. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/110/4/042033.

. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/110/4/042033. - Bauer, T. H.; Spital, R. D.; Yennie, D. R.; Pipkin, F. M. (1978). “The hadronic properties of the photon in high-energy interactions”. Reviews of Modern Physics. 50 (2): 261. Bibcode:1978RvMP…50..261B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.50.261.

- Sakurai, J. J. (1960). “Theory of strong interactions”. Annals of Physics. 11: 1. Bibcode:1960AnPhy..11….1S. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(60)90126-3.

- Walsh, T. F.; Zerwas, P. (1973). “Two-photon processes in the parton model”. Physics Letters B. 44 (2): 195. Bibcode:1973PhLB…44..195W. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(73)90520-0.

- Witten, E. (1977). “Anomalous cross section for photon-photon scattering in gauge theories”. Nuclear Physics B. 120 (2): 189. Bibcode:1977NuPhB.120..189W. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(77)90038-4.

- Nisius, R. (2000). “The photon structure from deep inelastic electron–photon scattering”. Physics Reports. 332 (4–6): 165. Bibcode:2000PhR…332..165N. arXiv:hep-ex/9912049

. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(99)00115-5.

. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(99)00115-5. - Ryder, L.H. (1996). Quantum field theory (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47814-6.

- Sheldon Glashow Nobel lecture, delivered 8 December 1979.

- Abdus Salam Nobel lecture, delivered 8 December 1979.

- Steven Weinberg Nobel lecture, delivered 8 December 1979.

- E.g., chapter 14 in Hughes, I. S. (1985). Elementary particles (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26092-2.

- E.g., section 10.1 in Dunlap, R.A. (2004). An Introduction to the Physics of Nuclei and Particles. Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-39294-6.

- Radiative correction to electron mass section 7-1-2, anomalous magnetic moments section 7-2-1, Lamb shift section 7-3-2 and hyperfine splitting in positronium section 10-3 in Itzykson, C.; Zuber, J.-B. (1980). Quantum Field Theory. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-032071-3.

- E. g. sections 9.1 (gravitational contribution of photons) and 10.5 (influence of gravity on light) in Stephani, H.; Stewart, J. (1990). General Relativity: An Introduction to the Theory of Gravitational Field. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86 ff, 108 ff. ISBN 0-521-37941-5.

- Naeye, R. (1998). Through the Eyes of Hubble: Birth, Life and Violent Death of Stars. CRC Press. ISBN 0-750-30484-7. OCLC 40180195.

- Polaritons section 10.10.1, Raman and Brillouin scattering section 10.11.3 in Patterson, J.D.; Bailey, B.C. (2007). Solid-State Physics: Introduction to the Theory. Springer. ISBN 3-540-24115-9.

- E.g. section 11-5 C in Pine, S.H.; Hendrickson, J.B.; Cram, D.J.; Hammond, G.S. (1980). Organic Chemistry (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-050115-7.

- Nobel lecture given by G. Wald on December 12, 1967, online at nobelprize.org: The Molecular Basis of Visual Excitation.

- Photomultiplier section 1.1.10, CCDs section 1.1.8, Geiger counters section 1.3.2.1 in Kitchin, C.R. (2008). Astrophysical Techniques. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 1-4200-8243-4.

- Denk, W.; Svoboda, K. (1997). “Photon upmanship: Why multiphoton imaging is more than a gimmick”. Neuron. 18 (3): 351–357. PMID 9115730. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81237-4.

- Lakowicz, J.R. (2006). Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer. pp. 529 ff. ISBN 0-387-31278-1.

- Jennewein, T.; Achleitner, U.; Weihs, G.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. (2000). “A fast and compact quantum random number generator”. Review of Scientific Instruments. 71 (4): 1675–1680. Bibcode:2000RScI…71.1675J. arXiv:quant-ph/9912118

. doi:10.1063/1.1150518.

. doi:10.1063/1.1150518.

Stefanov, A.; Gisin, N.; Guinnard, O.; Guinnard, L.; Zbiden, H. (2000). “Optical quantum random number generator”. Journal of Modern Optics. 47 (4): 595–598. doi:10.1080/095003400147908.